An abridged history of the placebo effect

You aren’t likely to find a more loaded term than the placebo effect. As one author pointed out, it has the quality of a semantic chameleon, signifying different things in different fields of study. To the scientists, it’s a nuisance: something that must be overcome in a research study in order to prove that a treatment ‘really works’. To the doctors — the orthodox ones, at least — it’s a happy mistake: a phenomenon that contributes to well-being, but which is for the most part evoked without their intention. To the philosophers, it’s a contradiction in terms: how can an inert substance nonetheless be active?

The popular understanding of a placebo is this: a treatment which the giver doesn’t expect to have any effects, but which nonetheless does, due presumably to the beliefs of the user.

This definition is healer-centric: it implies that the placebo is given knowingly. However, there are plenty of cases where the placebo affect is elicited without any intention. For that reason, we can broaden our definition and say: the placebo effect is any therapeutic outcome which results from the beliefs of the patient.

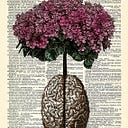

This conception of the placebo effect as a kind of ‘belief effect’ is a useful one, because it allows us to see how it may have manifested even before the advent of modern medicine.

The earliest form of health care was delivered by so-called medicine men, also known as shamans. These spiritual guides, who were sometimes assisted by the power of psychedelic drugs, relieved the sick from what were considered spiritual afflictions: possessions by demons, oppressions by curses, and so on. That shamans existed for thousands of years across many cultures is a testament to the healing power of culturally conditioned mythopoetic narratives, and the beliefs and expectations that they engender.

Developments away from a spiritual conception of health (or, more cynically, superstitious belief systems) occurred in ancient Greece and China. The Greeks developed a theory of four humors whose relative amounts in the body could affect one’s health. The Chinese, on the other hand, developed an idea of qi, sometimes translated as life-force, which followed meridians in the body and whose flow could be blocked. Although these conceptions of bodily functioning appear outdated to us now, they were revolutionary in that they ascribed physical causes to disease.

Thoughout this time, healers did have a variety active substances which must have been eliciting real physiological affects on the body. The bark of the willow tree, for example, was used for thousands of years as a pain-reliever, and is now known to contain the active substance found in Aspirin. Some surgical procedures, such as couching to remove cataracts, were also medically sound.

However, even considering the shift towards a more physicalist view of the body brought on in the West by the Greeks, most of the repertoire of healthcare prior to the 19th century was at best inactive and at worst dangerously harmful. We only need to reflect on the prevalence of such techniques as trepanning and blood-letting in order to remember tha preferred healthcare interventions were far from having any real therapeutic effect.

With modern medicine also came a conception of the placebo. The word itself derives from a liturgical hymn which would be sung in memory of a deceased person, often by a person who came to into church only for the benefit of food and shelter. For that reason, the term became synonymous with a sycophant, yes-man, or deceptive flatterer.

As medicine became more empirically-based following the scientific revolution, doctors found themselves in a position of giving a patient inert substances like water or bread simply to please them and quell their concerns. The deceptive element of this act, which Ben Franklin once described as a ‘pious fraud’, was then given the name placebo, which brought on the connection of this term with medicine.

The rise of the placebo effect as an aspect of medical research came with the work of Henry Beecher in the 1950s. Beecher was a military doctor who noticed that soldiers would often experience pain relief even when less, or even no, morphine was being administered to them. He attributed this to two things: first, the hospital environment was more welcoming than the battlefield (compare this to the average person’s conception of a hospital, which signifies death and disease). But also, Beecher believed that the soldier’s expectation was causing them to experience relief of pain, when no exogenous drug was being administered.

Returning from war, Beecher authored a seminal paper called “The Powerful Placebo”. Although its research methods have since been criticized, it remains a powerful testament to the subjective improvements in health which can be affected by an inert substance.

In the second half of the 20th century, the placebo effect was inducted into the so-called ‘golden standard’ of medical research: the randomized control trial. In order to demonstrate the efficacy of a medical intervention, it must be shown to do better than the placebo effect in one of these trials. In this context, the placebo effect simply means any therapeutic outcome which is not caused by the treatment of interest.

For the most part, this conception of the placebo effect has remained with us into the 21st century. However, with the rise of alternative medicine and attempts at more ‘patient-centered’ approaches to health care, we may be witnessing a cultural shift with regards to this concept, which will transform it beyond simply an artifact to be dealt with my medical researchers and into a powerful therapeutic tool to be utilized by clinicians. After all, as one researcher put it, the history of medicine appears to be the history of the placebo effect: for a majority of treatments administered in a majority of time-periods, ranging from the mystical chants of the shaman to the diligent blood-letting of the medieval barber, the therapeutic effect wasn’t so much a matter of active substances, but rather, the act of a healer taking care of a sick person in an encouraging and empathetic way.

This aspect of healing, which can serve as a potent supplement to physiologically-active ones, is what should be emphasized by health care today, and what will likely cause us to shift our cultural attitude towards the ubiquitous and mysterious placebo effect.