Are humans just animals, or something more?

Our eternal quest to distinguish ourselves from nature

The following poem is found in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel, Cat’s Cradle:

Tiger got to hunt,

Bird got to fly.

Man got to sit and wonder,

“Why, why why.”Tiger got to sleep,

Bird got to land.

Man got to tell himself he understand.

The last line presents a somewhat cynical view that folly is a central part of the human experience: our ability to rest (to sleep … to land …) comes only by telling ourselves we understand. But the simple message of this poem is this: humans and animals are up to very different things.

My friend recently wrote a philosophy paper on the topic of animal minds. Are the mental contents of humans that much different than those of animals? She critiques an argument put forth by the philosopher John Searle that animals posses the capacity for consciousness, intentionality, and thought processes. These are defined as:

- The capacity to have a subjective experience, what it’s like to be you, me, a bat, or an amoeba (consciousness)

- The capacity to act in the world with forethought and in anticipation of a future state of affairs (intentionality)

- The capacity to experience an inner world of thoughts and ideas that are ordered in a rational way (thought processes)

Now, it’s clear that humans engage in all these things. Consider the following example: a person is suddenly overcome by all the enticements of a cake — its smell, its taste, its texture—and so creates the object of their spontaneous craving. In this short sequence of events we find all three capacities at play: consciousness, intentionality, and thought processes.

But it is the additional belief of Searle that all three attributes are also possessed by animals. By arguing this, Searle implies that there is nothing fundamental that distinguishes them from humans— going against major philosophical precedents.

To what extent is it valid to compare human and animal experience? And what bearing, if any, should this have on our lives?

When the philosopher Rene Descartes described animals as automata, completely mechanical processes lacking any awareness or intentionality, he was speaking to a prevailing idea that only humans could possibly possess minds in the way we intuitively understand them.

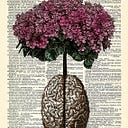

Searle’s biggest reason for rejecting this view is the biological continuity between humans and animals. There is such a similarity between the general structures of the chimp and human brains, for example, that it seems absurd not to believe the basic mental phenomena they create are shared by the two species.

And yet, some believe that humans are the possessors of some faculty — typically, a mind or soul — that distinguish them from animals. This is symbolized in the classical definition of humans as rational animals: though we may possess an anatomy similar to animals, we are nonetheless distinguished by some rational ability.

What might this faculty look like? There are a couple of options.

Inhibition over ‘base’ instincts

One very intuitive idea is that although humans and animals share the same underlying drives— to eat, to copulate, to seek shelter — humans are the only creatures capable of inhibiting these drives. According to Fruedian psychoanalysis the only way that humans can organize themselves socially is by either repressing or sublimating — that is, reorienting — their basic instincts.

The extreme of human inhibition comes from the so-called ascetics: those who have renounced worldly pleasures, typically for religious reasons, and lead a life of discipline and subdued passions. It seems difficult, we think, to find an animal correlate of this: instead, they are forever bound to their innate tendencies. There are no Buddhist monk beavers who have renounced their proclivity for collecting wood.

A sophisticated language

The word ‘sophisticated’ is a necessary qualifier here because there are well-studied forms of communication between some animals, like the mating calls of birds or the flower-detecting dance of bees. But in contrast to these basic forms of communication, when we consider the richness of human language and the diversity of things it can express, we might rightly feel that this gives us a special place in the animal kingdom.

Self-reflection; free-will

We might concede that animals think and feel; but it’s another thing entirely to know that you’re thinking and feeling. This is known as self-reflection.

To use a simple example, consider a rash and easily-provokable person, maybe someone with an anger management problem, who is taken by the throws of his passion to do things that he will later come to regret. We contrast them with a more rational person who is able to self-reflect and act intelligently, subduing his impulsive emotions.

Following this example, we might say that animals are ‘taken fully’ by their thoughts and emotions, such that they are like trains following a preordained track. We can also describe this by saying that only humans possess free-will: the capacity to choose between multiple courses of action.

Existentialism; mortality

This one is probably my favorite, mostly because it reverses the general trend that humanity’s distinguishing characteristics are in some sense positive or advantageous. On the contrary, we might posit that what sets us apart from animals is simply our ability to worry ourselves to death, over death.

So then, not only is there no Buddhist monk beaver, but there also isn’t a Kierkegaard beaver who questions the point of collecting wood in the first place.

All the preceding ideas are ways that someone might distinguish humans from animals. But why the need to do so in the first place?

I think that when the members of the earliest human civilizations looked at an animal they were filled with morbid fascination. Here is a creature who is not only largely unaware of its surroundings, having little control over nature, but is completely separated from entire realities that we recently uncovered: mathematics, social planning, narrative structure…

In other words, I think that animals have always reflected our limitations as humans. We look at them and secretly think: what if we are just as clueless as they are? Since we know realities that are outside of them, could there be realities that are outside of us? And this must have been such an unpalatable idea that philosophy was strained to find some essence of the human experience that distinguished us from ‘the brutes’.

On the contrary, we shouldn’t shy away from the possibility that we share with animals our utter inability to grasp the Universe — in fact we should be thrilled by it. Maybe if we accepted this truth, we would have the right attitude towards the world: that it isn’t something to be conquered by the intellect, or even necessarily a puzzle to be solved, but rather, a mystery to be appreciated.