Curb your hysteria: what Larry David teaches us about psychoanalytic theory

Larry David’s highly successful series Curb Your Enthusiasm features an only somewhat exaggerated version of himself: an unapologetic, unfiltered man who invariably gets into trouble by breaking social etiquette. While these incidents usually present us with simple lessons, Larry’s transgressive attitude in the season 9 episode Foisted! has unmistakably theoretical undertones, providing us with a good example of the psychoanalytic concept of hysteria.

Like many others, this episode begins with a minor faux-pas. Larry walks into a building and notices that a woman is following some distance behind him. He briefly considers holding the door open for her, but after giving her looks a glance appraisal, decides against it — leaving the door to shut abruptly in the woman’s face.

The woman is offended by Larry’s behavior, and doesn’t shy away from confronting him. He very plainly tells her that based on her olive vest, tie, and short hair, he assumed that she wouldn’t have appreciated a chivalrous gesture—and in fact, refrained from doing so out of consideration for her. The woman isn’t impressed by this explanation, even when he offers distance as an ancillary factor, and she leaves him with a few expletives before walking away.

A chance encounter brings Larry and the woman, Betty, back together, as she cuts his hair. She mentions that she’ll be marrying a woman soon, and that she’s chosen to be the bride while her wife is the groom. This surprises Larry, and upon seeing that her soon-to-be-wife is more traditionally feminine, he insists that their roles should be reversed. This opinion is seconded by Larry’s friend and roommate Leon, who can only remark on seeing a picture of her future wife: “Now that’s a bride!”.

By the end of the episode, we learn that Betty has become deeply affected by Larry’s comments, and she decides that she wants to be the groom at her wedding after all. This causes a conflict with her wife, who insists on being the groom herself, and this disagreement escalates to the point that they separate. Their broken relationship has become the latest victim of Larry’s unflinching tendency to tell the truth: in this case, to point out a mismatch between Betty’s self-identity and the way that she’s perceived.

The word ‘hysteria’ derives from the Greek word ‘uterus’, reflecting an ancient belief that a woman could suffer from diseases caused by the movement of her uterus around her body. In middle-age Europe, hysteria was used as a general term for a variety of symptoms including headaches, dizziness, general restlessness, and abnormal appetite or sexual desire, the combination of which was presumed to be caused by an innately feminine source.

By the 19th century, the ‘wandering womb’ hypothesis was abandoned, and hysteria became a diagnosis applied to any neurological symptom for which a specific biological cause couldn’t be found. This makes it one of the earliest examples of a ‘psychosomatic’ disorder, which refers broadly to any bodily illness which is strongly influenced by the patient’s psychology and emotional life.

Freud’s early clinical experience consisted almost entirely of women who would have been diagnosed with hysteria. Around the turn of the 20th century, Freud developed the psychoanalytic theory of hysteria, which can briefly be summarized by his remark that hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences. Freud concluded that hysterics have unresolved, emotionally-charged memories which they are driven to talk about, deliberate on, and act out throughout the course of their therapy. By so doing, they are able to therapeutically reengage with the pathos whose repression had been contributing to their bodily symptoms. As one of the earliest patients of psychoanalysis deemed it, this was “the talking cure”—as Freud himself called it, it was the cathartic method.

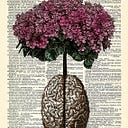

The psychoanalytic concept of hysteria was further elaborated on by Jacques Lacan, a Parisian psychoanalyst who reformulated many of Freud’s ideas using French structuralism and linguistics. For Lacan, the diagnostic criteria of hysteria wasn’t along the lines of individual symptoms, but rather, it described a certain structure of the psyche. Specifically, the structure of the hysteric takes the form of a question: “What is a woman?”, or more broadly, “Who am I?”. In declaring this to be the underlying conflict motivating the hysteric, Lacan situates hysteria in terms of the woman’s identity. We could say that while Freud thought of hysterics as suffering from reminisces, Lacan said that they were suffering chiefly from a crisis of identity, with their exaggerated and often-times theatrical bodily symptoms constituting a call for recognition and self-clarification.

Understood from the Lacanian perspective, we can say that Larry ‘hystericizes’ Betty. By conveying to her that her ‘type’ precludes such things as having a door opened for her or being the bride at her wedding, he causes her to question her identity. Slavoj Zizek, a philosopher and popularizer of Lacanian theory, suggests that this self-questioning can be conceived along the lines of the subject’s relationship to the symbolic mandate. For Zizek, the question that underlies hysteria is: “Why am I what you’re telling me I am?”, and is directed in a clinical setting at the psychoanalyst.

Under this conception, Betty becomes hystericized when she confronts the fact that her identity is inextricably dependent on the way that society perceives her. She finds herself in a situation where Larry’s understanding of womanhood, which represents broad societal attitudes and conceptions, conflicts with her own self-image. We can find plenty of casual examples of such a situation. On the receiving end of a stilted and overly-rehearsed pickup line, a girl may casually remark: He wasn’t hot enough for that. More controversially, a transgender woman who doesn’t ‘pass’ will be told, even by the most sympathetic ally, that she must put in some minimal effort to conform to society’s prevailing notions of womanhood in order to achieve the satisfaction she seeks.

In fact today, in our era of ‘identity politics’, the hysterical position is an undoubtedly radical one, which allows us to examine the unreflecting assumptions that underly our social relations. It will just take the work of more Larry David’s to hystericize the public.