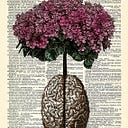

Introducing the ‘psychedelic bro’

What a guy I met at a party taught me about magic mushrooms

A poorly-lit room with cheap beer and reckless dialogue, i.e. the average American house party, is often the best setting to learn about people. I recently had a memorable encounter with a fellow party-goer whose comments spurred some reflection about psychedelic culture and drug use.

Gathered in the basement of my buddy Michael’s house, a couple of friends and I started discussing topics that guys in their early 20s are naturally predisposed to: girls, money, sports, and drugs. When this last topic came around, we shared our experiences with weed: our first time smoking it, its effects, people we considered addicted, and the nature of addiction.

It’s a rule of thumb that any conversation about weed will eventually include harder drugs, and sure enough, we soon found ourselves discussing acid and magic mushrooms. At this point, those veterans who had taken them gained some prominence in the dialogue as they fondly narrated their experiences — with no less pride than those pertaining to our first topic of conversation.

Finally, one guy in particular spoke up, beaming, about his last time tripping on mushrooms. He told us about the kaleidoscope world of shapes and colors that had suddenly been opened up to him, and the important insights (since irretrievable) that he comprehended on that fateful day. He related how walking in the park became a trek across the universe, the plants like shimmering alien life-forms urging him on in a cosmic conspiracy of care and good-will, elevating him to previously unattainable heights.

But the greatest achievement and apex of the trip, he assured us, was the dissolution of his ego. He spoke almost religiously of the self-effacing properties of the drug, which allowed him to glimpse an all-pervasive and innate unity that transcended our deeply-rooted dichotomy between subject and objects — an experience typically restricted to the ecstasies of the most practiced religious mystics.

Here the eyes of his audience widened — but as for myself, I couldn’t help but chuckle! Here was a person who was stroking his ego, prominently and unashamedly, by discussing the death of his ego: a person who, in service of his ego, swore by the very same ego’s unreality. And with this curious paradox was my inaugural experience of the psychedelic bro.

Psychedelic culture. In some sense this phrase is a contradiction in terms. Isn’t the point of psychedelics to shatter culture, to imbibe a person with a renewed individuality that they can wield, fresh-eyed and fearless, against oppressive father Law and restrictive father Custom?

And yet as anyone acquainted with the Internet knows, there’s a sizable community of so-called ‘psychonauts’, those amateur phenomenologists who share notes about their psychedelic trips. Their efforts have resulted in a living encyclopedia, mostly of forums but also of several online databases, that are encapsulating the psychedelic experience with an almost scientific rigor.

But not all aspects of this ‘culture’ are that precise. A less well-formulated position is taken by what I call the psychedelic bro, that enthusiast who beyond just partaking in the drug has a committed but somewhat nebulous attitude towards it. Vague as it is, it isn’t lacking in vigor: the psychedelic bro will speak enthusiastically about the mind-expanding effects of such drugs as LSD, psilocybin, and DMT. They might also make references to ancient civilizations, Joe Rogan, and the emergence of human consciousness.

How can we explain this peculiar archetype? The widespread use of psychedelics, barely 60 years old now, is a cultural phenomenon that stands in a definite relation to contemporary ideas.

The resurgence of religious/spiritual thinking

Religion has gone by the wayside; the era of prophets is over and ‘the veil has been lifted’, so to speak. Especially among the youngest generations, it’s no longer fashionable to speak of God or heaven, even when discussing virtues or miraculous events.

On the other hand, a person is given significant leeway if they simply replace those religious topics with references to the spiritual destinations opened up by psychedelics. If someone starts a sentence with, ‘at Church I had the sudden realization…’ then we’re either bored or skeptical, but if they start a sentence with ‘while tripping I had the sudden realization…’ then our ears perk up at the expectation of a good story.

In this way, discourse about psychedelics can be a stand-in for religious or spiritual talk. It has the advantage of being based on a definite phenomenon (the trip) which even has some rudimentary scientific backing (i.e. studies that suggest that certain drugs are associated with meaningful experiences or insights).

A response to scientism

Science, it seems, has reduced all the wonders of humanity — even consciousness itself — to the inert metrics of behaviorism and materialism. The psychedelic experience stands decidedly opposed to this trend, plunging the user into a world that can hardly be explained by language, let alone scientific notation.

In that way psychedelics afford us some freedom from the prevailing worldview of scientific materialism, insofar as they provide the conditions for an encounter that resists intellectual comprehension. Of course, we can always assert that it’s still just a matter of brain chemistry — but from the user’s perspective, this explanation is hardly adequate, a fact that underscores the inability of science to encapsulate human experience more broadly.

A shared culture

From politics to sports teams to TV shows, people love to get together in the spirit of shared enthusiasm; psychedelics are no exception. In fact this is true of all drugs: I remember two years ago, when Michigan moved to decriminalize marijuana, a stoner I met in Colorado congratulated me and declared that ‘we’re finally making it happen’.

I was frankly off-put by the man’s false presumption of a shared culture — it reminded me of that Vonnegut neologism, granfalloon, meaning a superficial identity — but from it I learned that drug culture can be a strong source of identity and coming-together.

So there’s a brief sketch of the psychedelic bro. Stereotyped as his appearance and opinions are, we can’t help but admire what he represents: a frat-boy style of mysticism, secular but vaguely spiritual, that sees the world on the precipice of a new cultural awakening. His hand is outstretched with the offer of drugs, an opportunity for good times and expansions of consciousness, and he speaks to you ‘from the other side’, hoping to induct you as one of his kind.

His understanding is no real understanding: it operates on the level of speech, not action. But still, it’s nice to hear his stories about tryptamine and clinical trials and stoned apes, and the hopeful enthusiasm with which he relates them. After all, the psychedelic bros are relics-in-the-making: the latest figures of our drug culture, the hippies of the (20)20s.