The alienated doctor

What Karl Marx can teach us about physician burnout

(This article was originally published on KevinMD)

Introduction

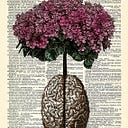

Professional burnout is widely identified using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which defines it along psychological lines: emotional exhaustion, a feeling of depersonalization and cynicism, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. Accordingly, the phenomenon of physician burnout — an increasingly prevalent and pressing concern in medicine — is often framed as a personal problem whose solution should come in the form of self-care. While this approach is undoubtedly helpful, it doesn’t sufficiently address the structural factors that contribute to burnout in the first place: namely, those resulting from the growing commercialization of healthcare. To that end, the capitalist critique of Karl Marx will be useful, and will allow us to understand physician burnout as the latest manifestation of what the communist philosopher called alienation.

The traditional conception of burnout

Popularly understood, physician burnout is a problem that affects the doctor as though it was a psychological disturbance. In his book Stop Physician Burnout: What to Do When Working Harder Isn’t Working, physician and executive coach Dr. Dike Drummond argues precisely this. The book, widely distributed to doctors by many hospitals and healthcare systems, encourages practitioners to utilize stress-reduction exercises like mindfulness and positive thinking, striking a healthy balance between physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being.

Implicit in this approach to physician burnout is the idea that individual-level factors are its primary causes. In a chapter titled What Causes Burnout? Dr. Drummond identifies multiple stressors like overworking, clerical work, and inflexibility of schedules that lead to the development of burnout in physicians.

This conception of physician burnout, which we might call the traditional one, doesn’t sufficiently address the underlying structural factors that contribute to it. These factors are related to the fundamental transformation that occurred in medicine around the second half of the 20th century: the commercialization of health care.

Commercialized medicine and its effects

In his book A Second Opinion: Rescuing America’s Healthcare, Dr. Arnold Relman takes the position that the commercialization of health care is contributing to the rising costs and stagnating efficiency of America’s healthcare system. He argues that the rise of private insurance companies, entrepreneurial physicians, and privately-owned hospitals has radically transformed the practice of medicine from a profession to something more closely resembling a business, resulting in an increase in expenditures and the attendant problems of access and quality that characterize our modern healthcare system.

In describing the effects of commercial interests and market economics on medicine, Relman documents how factors like reimbursement schemes have direct impacts on how doctors practice. One particularly strong and well-known example is the rise of high-level diagnoses after the implementation of diagnosis-related group based reimbursement systems. Another is the increasing tendency for primary care physicians to spend less time with patients in order to earn more money and meet hospital quotas.

What these examples illustrate is how structural-level influences like reimbursement schemes can affect the individual doctor’s experience, imposing certain restrictions and incentives on them that transform their practice. The rise of these influences, which emerge as a result of capitalist influences, are best understood using Marxist concept of alienation.

Marx’s concept of alienation

The commercialization of healthcare presents us with the perfect opportunity for Marxist critique. After all, it was the philosopher and political theorist Karl Marx who first undertook a description of how capitalist modes of production effected an entire class of workers, namely the proletariats who worked in factories. Today, we can use the same ideas to describe how capitalist influences on medicine are affecting another vocational group: doctors.

Marx describes how in a capitalist system, factory workers become estranged from the product of their labor. Whereas craftsmen feel deeply connected to their creations, which serve as forms of self-expression and testaments to the refinement of their art, factory workers — whose labor becomes increasingly fragmented, repetitive, and depersonalized — no longer feel pride in the fruits of their work, and identify very little with them.

They also become estranged by their own activity. To the proletariat, work is no longer a fulfilling means of self-expression or a source of meaning. Rather, it becomes a necessary condition of their livelihood; they find themselves tied to it not for any authentic desire on their part, but simply to satisfy basic personal needs and the requirements of their place of work.

Due to their estrangement from both the product and the activity of their occupation, proletariats are denied the chance to authentically relate to their work. This separation from the proletariat’s work and his authentic being is what Marx calls alienation.

Burnout as alienation

We might cautiously suggest that the position of doctors today, restricted as they are by a growing number of bureaucratic and profit-driven incentives for care, is approaching that of the proletariat in at least one way: the rise of alienation.

Just as Marx described how the capitalist mode of production influences the lived experience of the proletariat, so too can we examine how the commercialization of healthcare since the 1950s has left its mark on the physician in the form of burnout.

In the same way that the proletariat ties the significance of his labor in the value of the product, so too does the service that the physician provides become objectified by diverse metrics and health outcome measurements. Of course, these metrics provide doctors with important information like mortality rates and patient satisfaction, which are crucial for any successful practice. But something entirely different happens when these measurements, which are typically taken for the sake of profit margins, are pursued as the ultimate ends, rather than a means to perfect the quality of care delivered.

When a doctor’s motivation shifts from the pursuit of the patient’s well-being — an inherently subjective endeavor — to the fulfillment of objective metrics, he finds himself estranged from the products of his work: his contribution to society is reduced to a number, like a salesman who identifies their work in the amount of revenue they bring in.

Additionally, just as the proletariat’s work comes to lose meaning, so too can doctors become increasingly dissatisfied with how they practice, no longer feeling that their work reflects the goals and attitudes for which they pursued medicine in the first place.

A case study

In order to assess the usefulness of this conception of burnout, let’s apply it to a part of Dr. Drummond’s book. He argues that the rise of administrative responsibilities like documentation, billing, and other non-clinical factors are contributing to burnout by causing undue stress on the doctor. This is in line with the personal or psychological interpretation of burnout.

Conversely, understood through the lens of alienation, these factors are contributing to burnout not simply because they add to the physician’s workload, but because they interfere with the doctor’s authentic mode of practicing. In other words, these are factors which are alienating the doctor from themselves, detracting from their core occupation of diagnosing diseases and treating patients.

Conclusion

Physician burnout is commonly understood as an individual-level problem which benefits from psychologically-therapeutic approaches. But looking at the way that commercialized medicine has transformed the way doctors practice, it’s clear that there are structural factors which are relevant to the problem. The Marxist concept of alienation provides us with a framework to understand burnout as a necessary consequence of the regulations and restrictions imposed on the modern physician. Profit-driven motives, insurance reimbursement schemes, outcome metrics, and other factors have transformed the landscape of medicine in a way similar to the effect of industrialization on the working class: they are estranging the healthcare provider from their activity, themselves, and the overall culture of their practice.

The solution that this conception of burnout gives us is clear. Self-care cannot be the only antidote. Doctors are encouraged not only to safeguard their emotional well-being, but also to re-establish the original motivations that led them to pursue medicine in the first place, practicing in a manner that reflects their authentic desires. In other words, the solution to physician burnout is physician empowerment: a renewed effort to establish a form of medicine that is free from commercial interests.