The explanatory gap: why computers (probably) aren’t conscious

A breeze caresses your shoulder. Pitter-patters of rain beat gently on the roof. The setting sun dashes the horizon with red and purple hues. These experiences are so familiar to us, and yet, they comprise one of the biggest unsolved mysteries in science: the so-called ‘explanatory gap’.

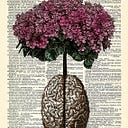

Science has been a useful tool in our quest to understand consciousness. For example, it has allowed us to understand the mechanics of color vision down to the level of retinal cells, photopigments, and brain circuitry. But something is missing from this stale anatomical story, something that science can’t seem to capture: the experience of color itself, what it’s like to see red, or blue, or green.

The explanatory gap is the name for this irreducible distance between our understanding — which is mediated by mathematical equations, physical laws, and so on — and our experience of the world.

Will this gap ever be bridged? The answer to this question has important consequences for psychology and computer science alike, as we’ll later see.

The Mary’s Room problem

Mary’s Room is a thought experiment that cuts to the heart of the explanatory gap. Philosopher Frank Jackson’s original description is worth the read:

Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor. She specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires, let us suppose, all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes, or the sky, and use terms like “red”, “blue”, and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal cords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence “The sky is blue”. […] What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a color television monitor? Will she learn anything or not?[4]

TL;DR — would a color-deprived scientist who learns everything there is to know about color be surprised to see red for the first time?

The intuitive response to the Mary’s room problem is to say yes, she does learn something new when stepping outside the room. It seems like no amount of knowledge could ever impart what it’s like to see red. Our experience of color seems to give us a unique kind of understanding that isn’t accessible even to the most accurate scientific description.

But others are not so sure. The two sides that have formed around this problem come to different conclusions about the explanatory gap:

Side 1: the idealists

Suppose you agree that when Mary leaves the room, she learns something new about color. This is notable, because she spent her time studying everything there is to know about color vision as a physical phenomenon. It would appear, therefore, that there are some forms of knowledge that aren’t reducible into physical parts.

What can we call this remaining surplus, the type of knowledge that resisted all the comprehensiveness of her scientific studies? Cognitive scientists have defined a term, qualia, to represent all those experiences which seem impenetrable to scientific explanation. These include emotions, sensations, color perception, and so on. We can find the correlates of these phenomena in our physiology, but we still cannot know why those biological processes would result in an experience in the first place.

The idealist bet: there are non-material realities that science will never encapsulate

So too, for the Greek philosopher Plato, we could speak of things beyond the physical: the Forms. The essence of every physical thing we observe through our senses was thought to be an imperfect reflection of a Form. For example, qualities like Beauty exist as a disembodied absolute category, and beautiful objects are simply partaking of this form of Beauty.

This idea is known as Platonic idealism; today, those who believe in the irreducibility of qualia might also be called idealists. This is because they attest to some territory ‘beyond the gap’: the realm of subjective experience, which cannot be explained in terms of physical reality.

Side 2: the physicalists

Suppose you disagree that Mary will learn anything new when she steps outside of the room. She would look at a tomato and say, “but of course, I knew what this experience would be like thanks to all my studies!”

According to this position, qualia can be reduced into material processes: there is nothing miraculous about experience that lies beyond the physical. Consequently, a good enough scientific theory will bridge the explanatory gap: it’s just a matter of perfecting our empirical techniques.

This is a hopeful position, because it maintains that someday, a comprehensive-enough understanding of the brain will tell us why everything — from the circuitry of color vision to the physiology of pain — results in what it’s like to have those experiences.

The physicalist bet: subjective experience will someday be reducible to material processes

Considering how much progress has already been made by science, it might be easy to side with the physicalists and bet on science. But we should always be suspicious of science’s ability to answer all questions. For example, we now know the physiological basis of thirst quite well, but we still don’t know why all those specific neurotransmitters cause the feeling of thirst.

Does qualia even exist?

Daniel Dennett is a neuroscientist and philosopher who has emerged as one of the most outspoken critics of the Mary’s Room thought experiment. He developed a thorough refutation of it in his book Consciousness Explained.

Dennett’s primary claim is that the problem is misleading: it assumes that learning ‘whatever there is to know about color’ is even comprehensible in the first place. For us to appreciate the sheer amount of information that total knowledge would entail, he invites us to think of RoboMary, a supercomputer in human form who ‘downloads’ all the information about color vision.

Once we think in terms of RoboMary, Dennett argues, it becomes much more intuitive to assert that the experience of red will not be surprising. After all, experiencing red is itself nothing more than a series of physical processes in the brain. So, if the robot is capable of learning enough about these processes, which occur in the minds of humans experiencing color, he can recreate these processes and therefore expect the experience of color.

In fact, for Dennett, what we call qualia is nothing but an illusion. The physical processes underlying subjective experience are simply too complicated for our language to convey: hence, the ‘mystery’ of qualia, and why science cannot seem to encapsulate it.

According to this view, there really is no ‘explanatory gap’: only puny humans in an unfathomably complicated system that lies beyond our comprehension.

Computer minds?

Let’s go back to RoboMary. If we can teach it the experience of red by uploading the relevant data, this suggests that qualia is indeed reducible to physical parts: circuits, 1s and 0s, and so on. If the computing power of a machine becomes sufficient to simulate human experiences, it seems we are forced to conclude that it is having experiences in the same way that a human is.

This means that someone who rejects qualia is saying something implicit about the idea of computer minds. For a machine working with a sufficient amount of data, it becomes meaningful to speak of a certain experience that is associated with information processing.

But let’s take a step back. You’re certainly aware that the physical processes in your own head are resulting in a conscious experience — you live it every day. But can we be certain that this is true of others? This is not a cheap plug for solipsism — the narcissistic philosophical idea that you are the only mind that exists. Rather, it’s a valid question that reveals the limitations of science.

The truth is, we cannot be certain that any other living thing is having experiences in the same way we are. It’s definitely the most likely scenario — if your brain creates consciousness, why wouldn’t a nearly identical one — but we still cannot point to a certain process or substance that comprises subjectivity.

So, computers will never be conscious in the same way that, from the perspective of cognitive science, we still can’t be 100% sure that anyone but yourself is conscious: we do not yet have a way to empirically demonstrate that anything is or isn’t conscious.

In other words, as long as the explanatory gap exists, we don’t have the basis to affirm that any computer or robot — no matter how advanced — is experiencing something.

This leads me to believe that our inability to understand consciousness is not so much a scientific conundrum, but rather a philosophical or even linguistic one. This is pretty exciting, because it means that some answers might be ‘under our nose’: correcting the right false assumption or investigating our definitions a bit more carefully might lead us to some profound conclusions.

Subscribe to my newsletter for updates on future articles: https://pages.convertkit.com/e8233d5800/cb92edd54d